The Sea is Our Ceremony, the Tomol is Our Song

The tomol is more than a canoe. It’s a symbol of who we are—proof that the Chumash were, and still are, ocean people. Of all the Indigenous communities in North American waters, only the Chumash, our southern neighbors the Tongva, and seafaring Pacific Islanders built something like this: a sleek, seagoing plank canoe, crafted not just to survive the ocean, but to move with it.

No one knows exactly where the word tomol comes from, but we believe it refers to how the boat is built—from the bottom up, plank by plank. Our ancestors gathered wi’ma, redwood that drifted hundreds of miles down the coast from the Pacific Northwest, seasoning in the salt and sun until it washed up on the shores of our Channel Islands and mainland. Lightweight, strong, and resistant to rot, this wood was a gift. And we knew what to do with it.

To seal the spaces between the planks, we used dogbane fibers—twisting them into cord, lashing the the planks together. Then we sealed it all with yop, a sticky mix of pine pitch and tar. Some tomol were small, just 8 feet long. Others stretched to 30 feet and could carry thousands of pounds. We used them to fish, to trade, to visit family on the Channel Islands. And much, much farther.

Building and paddling a tomol wasn’t just a skill—those who mastered it belonged to an elite guild called the Brotherhood-of-the-Tomol. They were respected, wealthy, and vital to our community’s survival. But Spanish colonization disrupted our lifeways, took our lands and waterways, banned our language, and tried to erase our traditions. A few Brotherhood members held on—like Palatino Saqt’ele, who continued under the control of the Spanish Missions—but over time, poverty and tragedy took their toll. By the early 1800s, the Brotherhood was nearly gone. So were the tomols.

But our story didn’t end there.

Helek: Return to the Sea

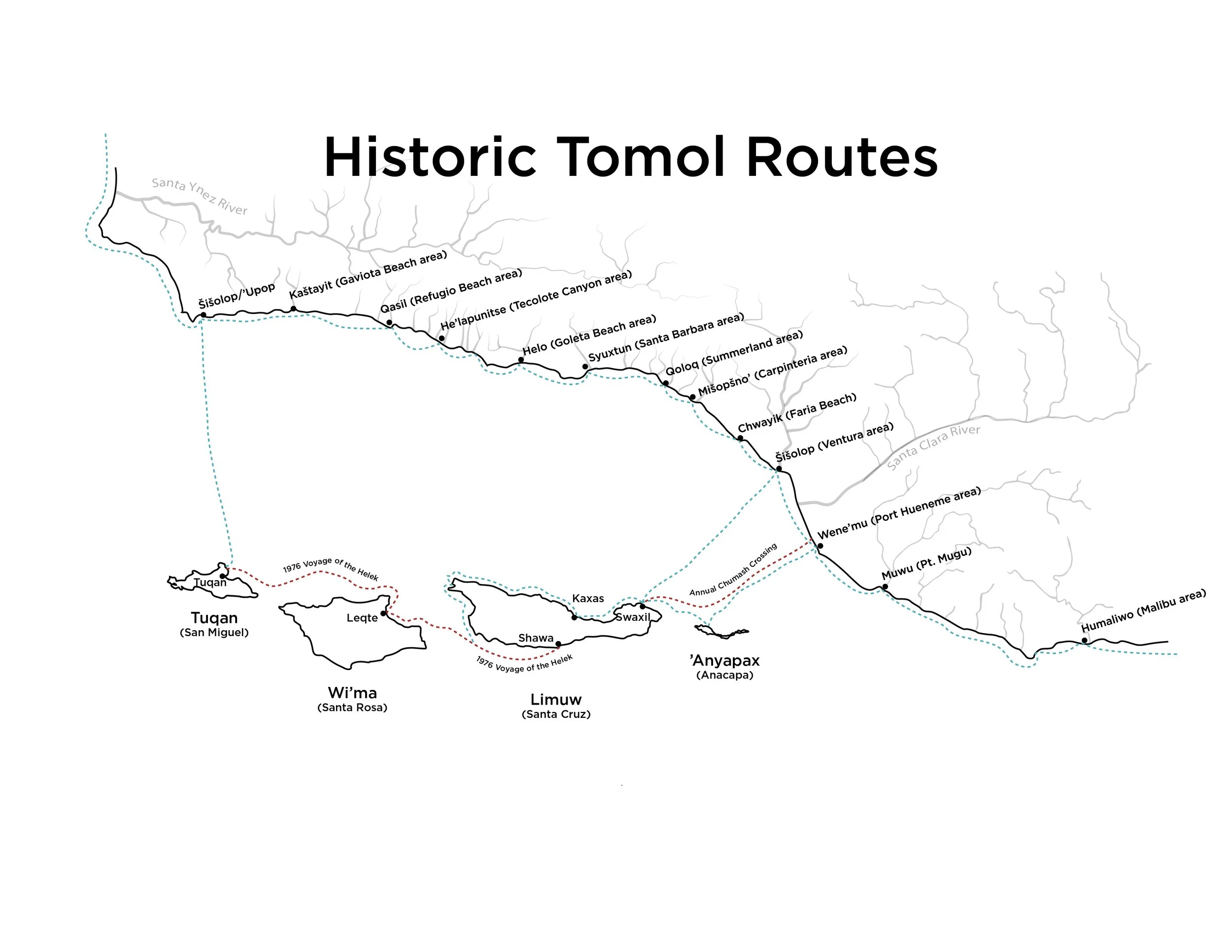

In 1976, as the country geared up to celebrate its 200th birthday, Indian Country had gained strength, allies, and connections through The Civil Rights Movement, the farmworkers’ movement, and the American Indian Movement. In a display of powerful cultural revival, the Hawaiians built and launched the Hokulea that year, inspiring Native maritime people across the globe. It was time to bring the tomol back.

Our community named her Helek—peregrine falcon (or hawk). And she would fly across the water.

John Ruiz, a descendant of Fernando Librado Kitsepawit—the last known member of the original Brotherhood-of-the-Tomol—teamed up with Travis Hudson, an anthropologist from the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History. Travis helped gather funding and resources. John focused on something harder: rebuilding trust. After years of displacement and discrimination, Chumash people had every reason to be cautious, especially with outsiders and institutions.

They brought in boatbuilder Pete Holworth. Harry Davis lent us his boatyard. But there was still a big question: how do you build a tomol? There were no step-by-step plans. Just fragments—over 500 pages of field notes from linguist John Peabody Harrington, who had recorded Kitsepawit’s knowledge decades earlier. Scribbled in multiple languages, filled with confusing measurements—fingerbreadths, palm widths, forearms. The team spent long nights decoding his notes, translating what our ancestor had said into something we could build from. Redwood driftwood was hauled out of the water from Vandeberg AFB to Santa Barbara, where the team spent long days cleaning tar off the wood so it could be milled into planks.

By early June 1976, Helek was ready. She stretched 26 feet, 9 inches, and could carry close to 2,000 pounds. And ten Chumash men were ready: Joseph Estrada Thot, Manuel Estrada Akhewo, Frank Gutierrez Kuic, Frank Gutierrez, Jr. Tomoloc, John Sespe Gutierrez, Raymond Chechihoh Gutierrez, Victor Slo’w Gutierrez, Kote Lotah, John Ruiz Thothokanayoh, and Alan Whitebear Sulwasunaytset. Ready to bring the Brotherhood-of-the-Tomol back to life, ready to care for the Helek, and ready to carry maritime knowledge forward for future generations. The Brotherhood gathered to test her along the coast, from East Beach in Santa Barbara, down to Carpinteria, and up to Summerland. The crew took the Helek out at Lake Los Carneros as well—to train, to prepare for the journey of a lifetime: an 11 day passage throughout our ancestral islands of Limuw, ’Anyapax, Wi’ma, and Tuqan.

On the morning of June 26, 1976, the Brotherhood launched from East Beach in Santa Barbara. A crowd gathered—elders, kids, families, the Mayor, museum folks, strangers. As our paddlers headed out into the blue, it wasn’t just about the ocean. It was about pride. It was about remembering who we were. The support vessel Just Love (Ernie Brooks’ boat) and the crew of the Helek spent eleven days navigating through the islands, sleeping on Limuw, Tuqan, and Wi’ma. On July 4th, 1976 they returned—up through Ventura, Carpinteria, Summerland, and finally…to Santa Barbara—with stories and a deep sense of identity, welcomed home by our community. In a display of support, Summerland residents came out in force to give the Brotherhood t-shirts with the words “Summerland Yacht Club.” That day, our community also participated in the United States Bicentennial Day Parade in Santa Barbara, sharing the wonders of the Helek with thousands of onlookers.

Nearly 50 years later, we still carry that memory of the Helek skimming the waves. That voyage sparked something deep in our people. Two decades after the Helek touched the water, our community built a community tomol—’Elye’wun. And our Chumash communities are still building: ’Alolk’oy, Yuxnuc, Iša Kowoč, Muptemi, Little Sister, Xax’ ’Alolk’oy, Milimolič hu ’Aqiwo’….

Because we are still here. Still seafaring. Still Chumash.

1975-1976: Coastal Band members John Ruiz, Manuel Estrada, Joann Dixon, and Darlene Garcia build the tomol with Pete Holworth and Travis Hudson. Here, the frame is complete, ready for redwood planks to be fitted around it. Harry Davis' boatyard in Santa Barbara. Photo: Charles de L'Arbe.

1975-1976: Laying redwood planks on at Harry Davis' boatyard in Santa Barbara. Pictured: Pete Holworth and Manuel Estrada.

1975-1976: The tomol rests upside down on the jig, its planks carefully laid, bound with cordage ties, and sealed with warm tar. It took 6 months to construct. Harry Davis' boatyard in Santa Barbara. Photo: Charles de L'Arbe.

1975-1976: Pete Holworth and Travis Hudson discuss the jig. Joann Dixon (Coastal Band) works on construction details. Harry Davis' boatyard in Santa Barbara. Photo: Charles de L'Arbe.

1975-1976: 9-foot double bladed paddles at Madeline Hall's (Coastal Band) home. These exquisitely carved blades are inlaid with red abalone patterns.

1975-1976: The tomol is given the name Helek, which means peregrine falcon. East Beach in Santa Barbara. Photo: Mehosh Dziadzio

May 1976: Our Chumash community has it's first launch from East Beach in Santa Barbara to Summerland. Pictured (left to right): John Ruiz, Manuel Estrada, Joe Estrada, Slo'w Gutierrez, Pete Zavalla, Frank Gutierrez. Photo: Ernie Brooks

May 1976: Our Chumash community has it's first launch from East Beach in Santa Barbara to Summerland. Photo: Ernie Brooks

May 1976: Our Chumash community has it's first launch from East Beach in Santa Barbara to Summerland. Photo: Ernie Brooks

May 1976: Our Chumash community has it's first launch from East Beach in Santa Barbara to Summerland. Photo: Ernie Brooks

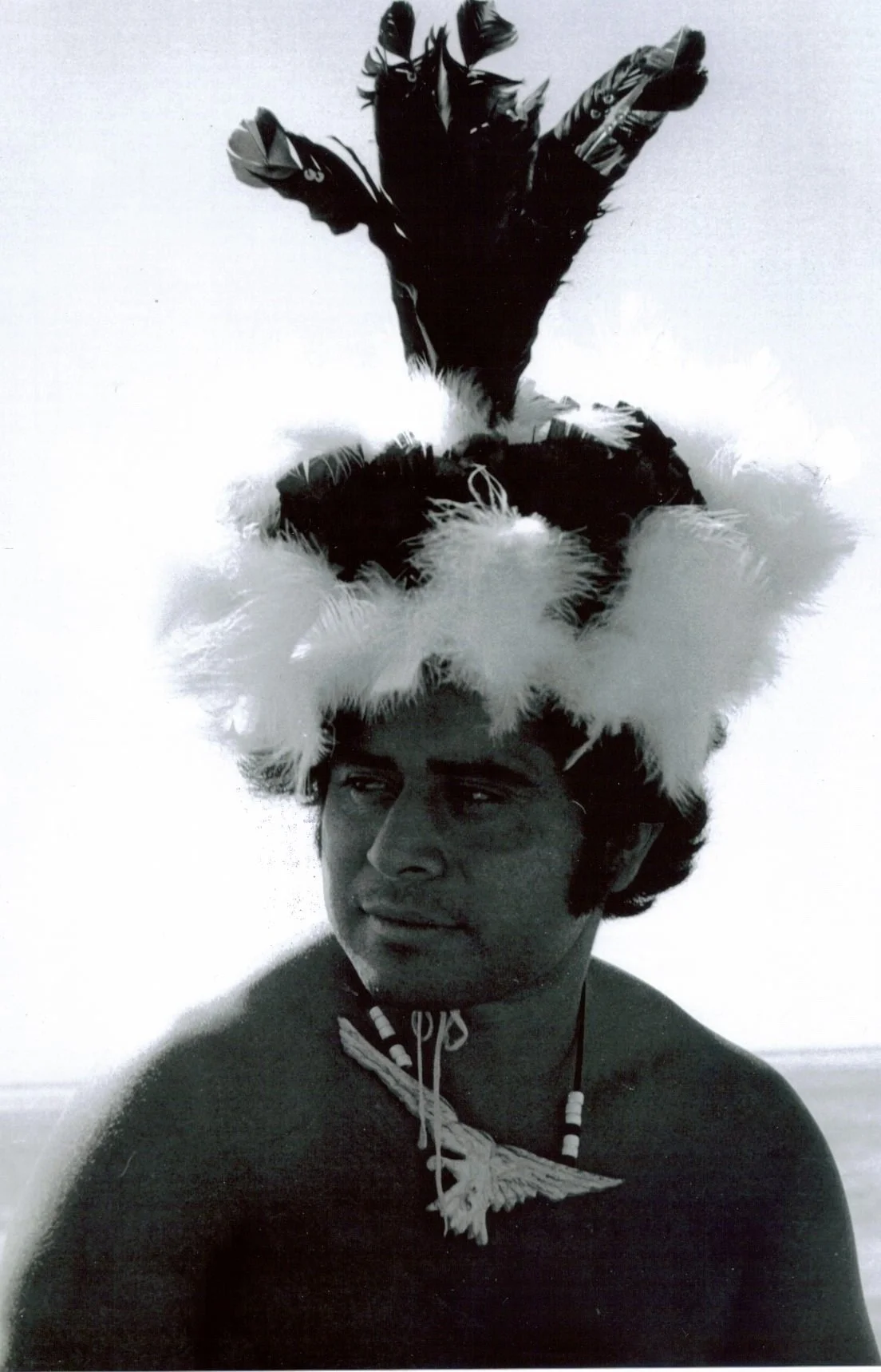

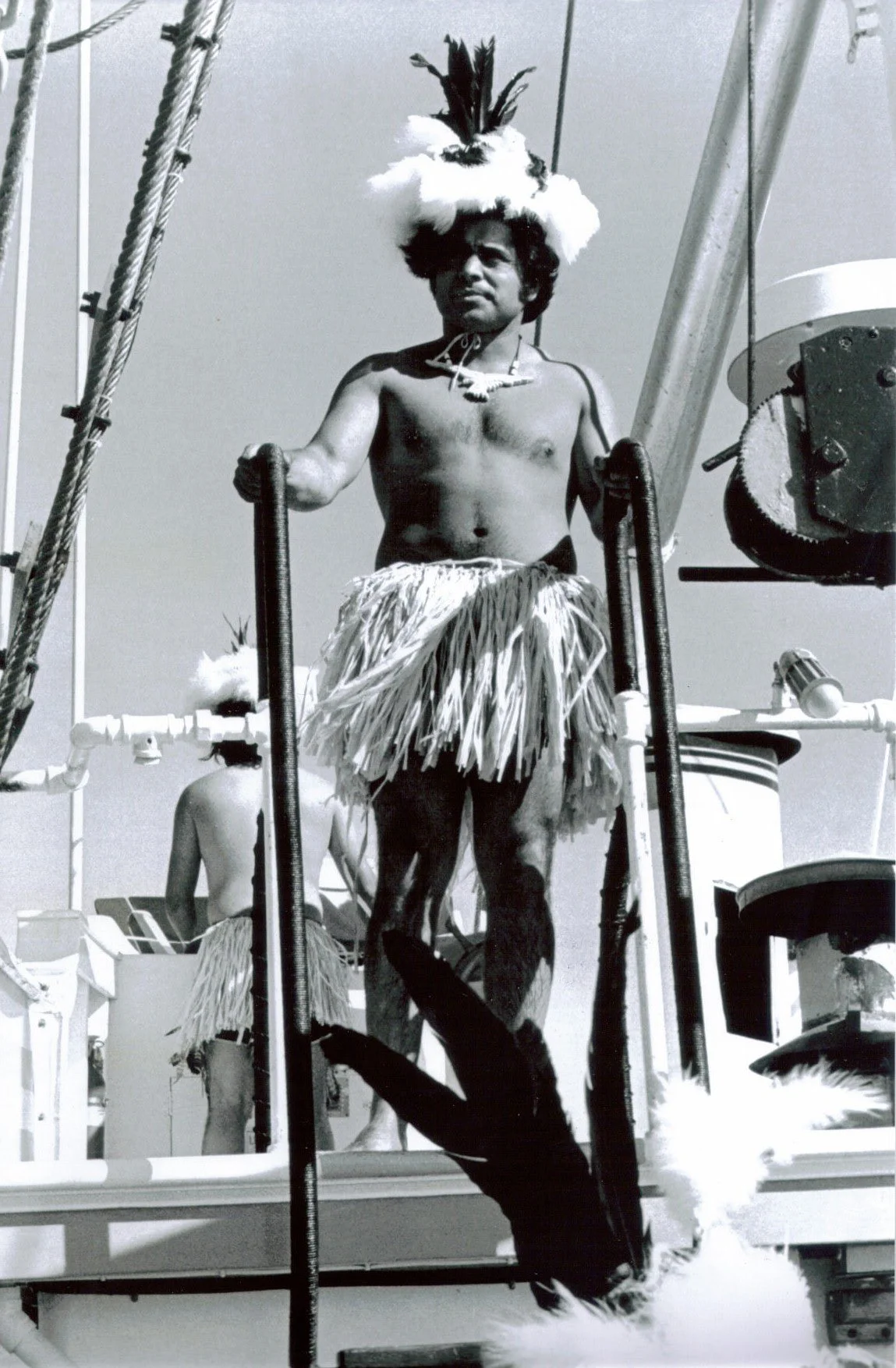

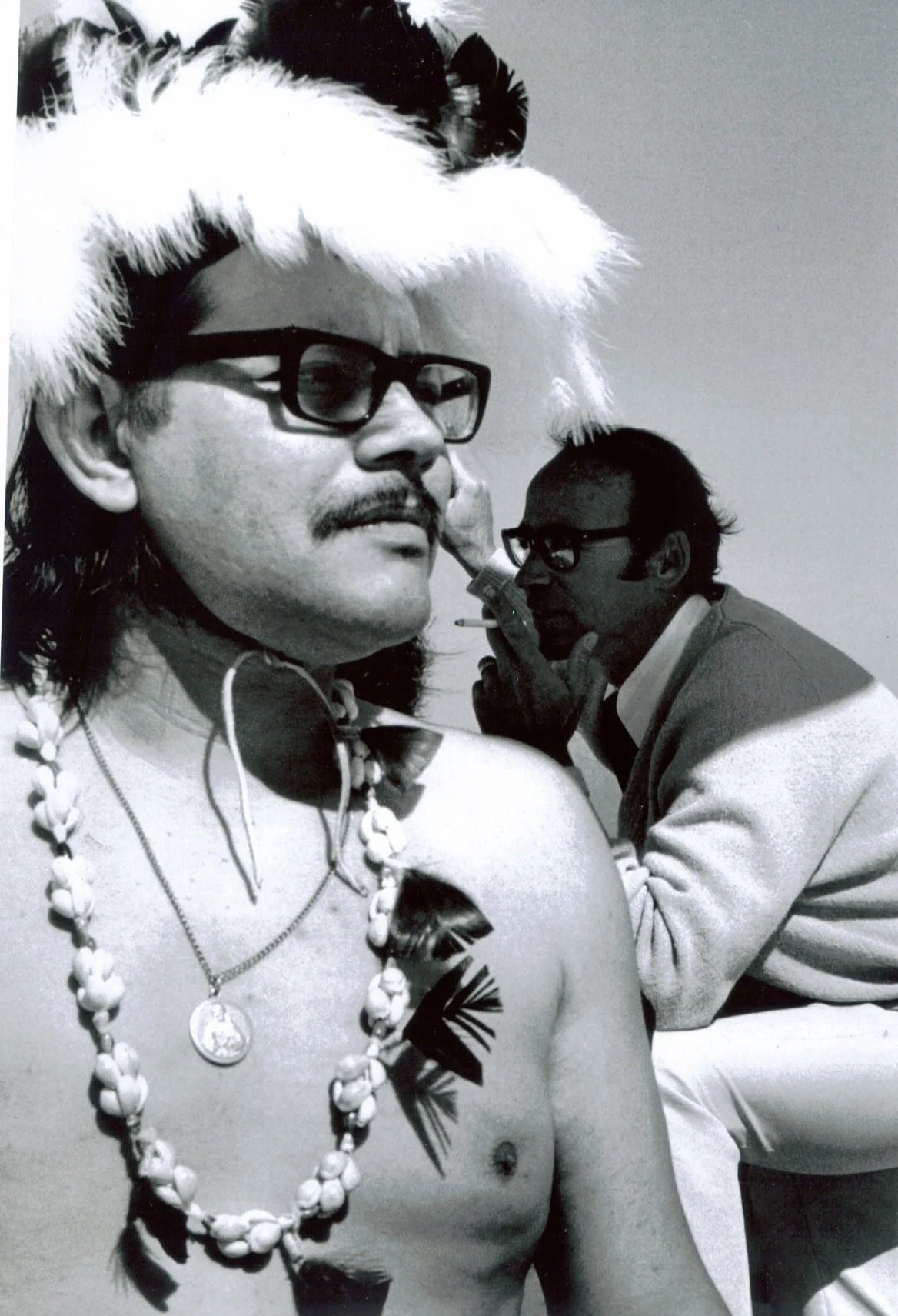

1976 Brotherhood-of-the-Tomol

May 1976: Practice at East Beach in Santa Barbara. Pictured (left to right): Kote Lotah, John Ruiz, Alan Whitebear, Frank Gutierrez Jr.

May 1976: Practice at East Beach in Santa Barbara. Pictured (left to right): John Sespe, Frank Gutierrez, John Ruiz, Alan Whitebear

May 1976: Practice at East Beach in Santa Barbara. Pictured (left to right): John Ruiz, Alan Whitebear, Frank Gutierrez

May 1976: Practicing on Lake Los Carneros, Goleta. Pictured (left to right): John Sespe, Manuel Estrada, Kote Lotah, Patsy Gomez, Slo'w Gutierrez.

June 1976: Practicing out into open waters of the channel near the oil derrick Platform A. Pictured (front to back): Kote Lotah, Alan Whitebear, Slo'w Gutierrez, Frank Gutierrez, Manuel Estrada, Joe Estrada, Photo: Ernie Brooks

June 1976: Practicing in the Santa Barbara harbor. Pictured (left to right): Joe Estrada, Kote Lotah, Slo'w Gutierrez, John Ruiz, Frank Gutuerrez, John Sespe, Manuel Estrada

June 26, 1976: Chumash community and the public gather at East Beach to see the Helek begin her 11 day journey throughout the Santa Barbara Channel Islands. Photo: Ernie Brooks

June 26, 1976: Chumash community and the public gather at East Beach to see the Helek begin her 11 day journey throughout the Santa Barbara Channel Islands.

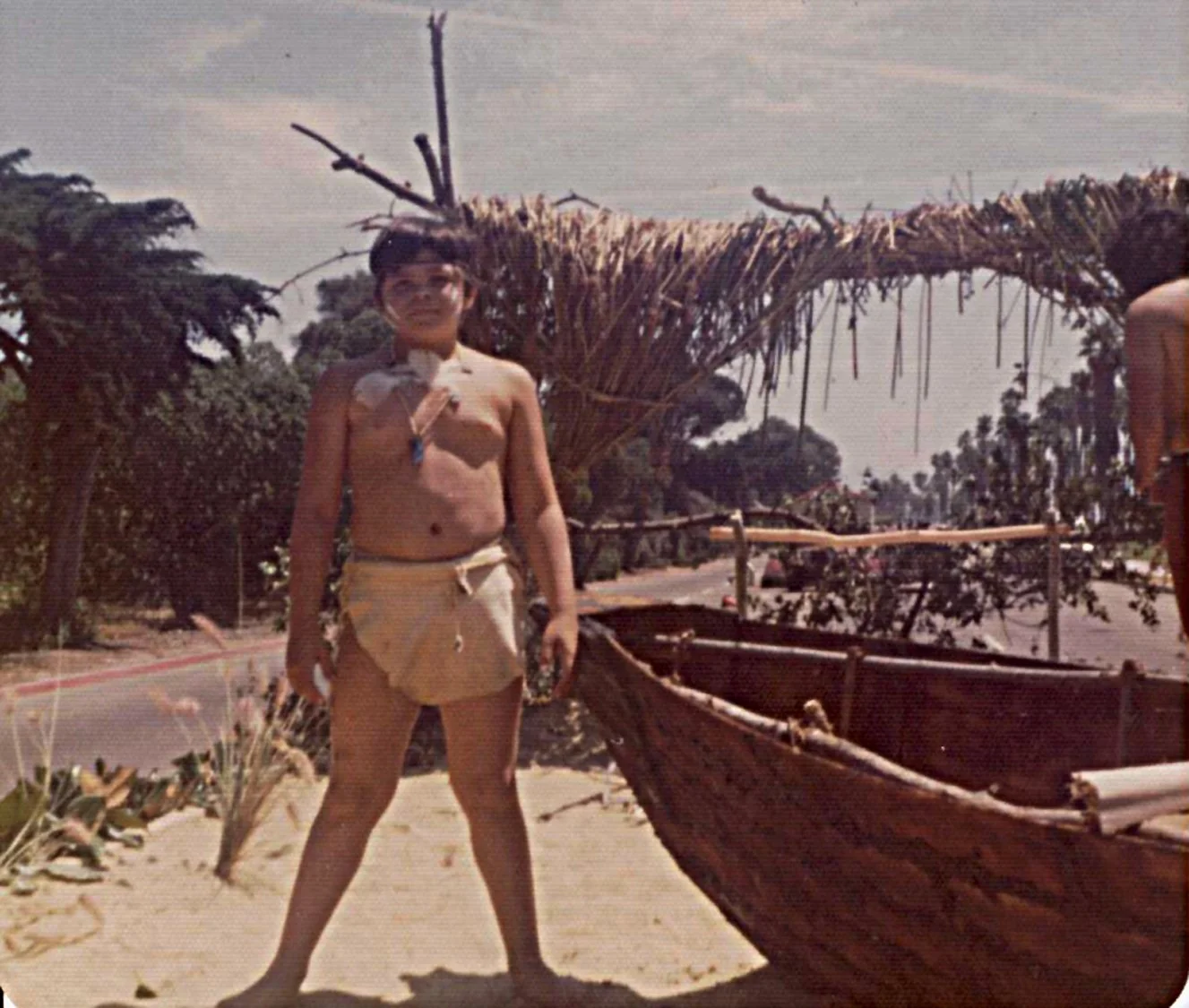

June 26, 1976: Chumash community and the public gather at East Beach to see the Helek begin her 11 day journey throughout the Santa Barbara Channel Islands. The crew puts her in the water while J.C. Ruiz (Coastal Band youth) blows a ceremonial conch.

June 26, 1976: East Beach launch. Beginning the 11 day journey throughout the Santa Barbara Channel Islands. Photo: Ernie Brooks

June 26, 1976: East Beach launch. Beginning the 11 day journey throughout the Santa Barbara Channel Islands. Photo: Ernie Brooks

June 26, 1976: East Beach launch. Beginning the 11 day journey throughout the Santa Barbara Channel Islands. Photo: Ernie Brooks

June 26, 1976: East Beach launch. Beginning the 11 day journey throughout the Santa Barbara Channel Islands. Photo: Ernie Brooks

June 26, 1976: East Beach launch. Beginning the 11 day journey throughout the Santa Barbara Channel Islands. Photo: Ernie Brooks

June 26, 1976: East Beach launch. Beginning the 11 day journey throughout the Santa Barbara Channel Islands. Photo: Ernie Brooks

June 26, 1976: East Beach launch. Beginning the 11 day journey throughout the Santa Barbara Channel Islands. Photo: Ernie Brooks

June 26, 1976: East Beach launch. Beginning the 11 day journey throughout the Santa Barbara Channel Islands. Kote Lotah pictured. Photo: Ernie Brooks

June 26, 1976: East Beach launch. Beginning the 11 day journey throughout the Santa Barbara Channel Islands. Photo: Ernie Brooks

June 26, 1976: East Beach launch. Beginning the 11 day journey throughout the Santa Barbara Channel Islands. Photo: Ernie Brooks

June 26, 1976: East Beach launch. Beginning the 11 day journey throughout the Santa Barbara Channel Islands. John Ruiz pictured. Photo: Ernie Brooks

June 26, 1976: East Beach launch. Beginning the 11 day journey throughout the Santa Barbara Channel Islands. Manual Estrada pictured. Photo: Ernie Brooks

June 26, 1976: East Beach launch. Beginning the 11 day journey throughout the Santa Barbara Channel Islands. Manual Estrada pictured. Photo: Ernie Brooks

June 26, 1976: East Beach launch. Beginning the 11 day journey throughout the Santa Barbara Channel Islands. Slo'w Gutierrez and Ernie Brooks on the support boat "Just Love". Photo: Ernie Brooks

June 1976: Crew of the Helek on their 11-day journey among the Santa Barbara Channel Islands. Photo: Mehosh Dziadzio

June 1976: Crew of the Helek on their 11-day journey among the Santa Barbara Channel Islands.

June 1976: Landing at the beach on the west side of Santa Cruz Island (Limuw). During the 11 day journey throughout the Santa Barbara Channel Islands. Photos: Ernie Brooks

June 1976: A beach on the west side of Santa Cruz Island (Limuw). During the 11 day journey throughout the Santa Barbara Channel Islands. Pictured: John Sespi, Frank Gutierrez, John Ruiz, Kote Lotah Photos: Ernie Brooks

June 1976: Open ocean between Santa Rosa Island (Limuw) and San Miguel Island (Tuqan). During the 11 day journey throughout the Santa Barbara Channel Islands. Pictured: Kote Lotah Photos: Ernie Brooks

June 1976: Open ocean between Santa Rosa Island (Limuw) and San Miguel Island (Tuqan). During the 11 day journey throughout the Santa Barbara Channel Islands. Pictured: Kote Lotah Photos: Ernie Brooks

June 1976: A beach on San Miguel Island (Tuqan). During the 11 day journey throughout the Santa Barbara Channel Islands. Pictured: Kote Lotah Photos: Ernie Brooks

June 1976: A beach on San Miguel Island (Tuqan). During the 11 day journey throughout the Santa Barbara Channel Islands. Photos: Ernie Brooks

June 1976: A beach on San Miguel Island (Tuqan). During the 11 day journey throughout the Santa Barbara Channel Islands. Photos: Ernie Brooks

June 1976: A beach on San Miguel Island (Tuqan) with the support boat "Just Love" in the background. During the 11 day journey throughout the Santa Barbara Channel Islands. Photos: Ernie Brooks

June 1976: A beach on San Miguel Island (Tuqan) with the support boat "Just Love" in the background. During the 11 day journey throughout the Santa Barbara Channel Islands. Photos: Ernie Brooks

July 1, 1975: Return journey from 11 day trip throughout the Santa Barbara Channel Islands. Ventura harbor is the first stop, then Summerland, Carpinteria, and finally Santa Barbara. The Ventura mayor greeted them with a fruit basket and watermelon.

July 1, 1975: Return journey from 11 day trip throughout the Santa Barbara Channel Islands. Ventura harbor is the first stop, then Summerland, Carpinteria, and finally Santa Barbara.

John Ruiz (2025) holds up the t-shirt that Summerland residents gifted to the paddlers of the Helek on their return from the 11 day trip throughout the Santa Barbara Channel Islands.

July 4 Fiesta Parade: Chumash community members Joann Dixon, Darlene Garcia, and Tina Gutierrez are part of the parade that feature the Helek and her crew.

June 1976: Chumash community pictured: Pat Gutierrez, Chita Pico, Maryanne Cunningham, Darlene Garcia, Kote Lotah, John Sespe, Manuel Estrada, Slo'w Gutierrez, Frank Gutierrez, Frank Gutierrez Jr., Joe Estrada, Tom Ruiz, Joann Dixon, Luis Gutierrez, Rhonda Barbin, George Barbin, Jimmy Bordin, J.C. Ruiz, George Gutierrez, Luis Gutierrez.

July 4 Fiesta Parade: Chumash community members Maryanne Cunningham, Darlene Garcia, and Tom Lopez are part of the parade that feature the Helek and her crew.

July 4 Fiesta Parade: The Helek and a few crew members (left to right) Kote Lotah, John Sespi, Joe Estrada, Slo'w Gutierrez, Frank Gutierrez.

July 4 Fiesta Parade: The Helek in the parade with youth J.C. Ruiz.

July 4 Fiesta Parade: The Helek in the parade with Tom Ruiz.

July 4 Fiesta Parade: Chumash community members are part of the parade that feature the Helek and her crew.

1976: The Helek at the Santa Barbara Indian Center at De La Guerra Plaza during a community gathering a month or so after the return journey. Pictured (left to right): John Sespi, Ray Gutierrez, Frank Gutierrez Jr., Frank Gutierrez, John Ruiz, Wonono Rubio, Slo'w Gutierrez, Manuel Estrada.

1976: The Helek at a Goleta beach community gathering a month or so after the return journey.

The video series below was created by the Northern Chumash Tribal Council. It is presented here through permission from Coastal Band members and co-creators Mike Khus-Zarate and John Ruiz.

The Helek had been funded by the Santa Barbara Natural History Museum and two months after she went on her 11 day journey through the Santa Barbara Channel Islands, the museum employed the Sheriff’s department to seize her from Elder Madeline Hall’s home. The museum placed her in their permanent exhibit—never to touch water again.

The spark lit by the Helek struggled to stay alive; without a tomol, our community had no means of sustaining this renewed bond with our ancient heritage. Cost was a huge barrier: building a redwood tomol can cost upwards of $30,000. We needed a funding partner, leadership, and a non-profit to house our tomol under.

In 1997, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and other organizations provided funds for Peter Holworth (who had worked with our community to build the Helek) along with leadership from Marcus Lopez (Barbareno Chumash Tribal Council) to build a new tomol for the community. Marcus Lopez, Roberta Cordero, Luhui Isha Ward, Julia Cordero, Cresensio Lopez, and Alan Salazar created the Chumash Maritime Association to legally house the tomol, care for the tomol, and to study, teach, and share Chumash tomol building and maritime culture. And Luhui Isha Ward, Marcus Lopez, and Julia Cordero secured permanent housing for the tomol at the Watershed Resource Center with the City of Santa Barbara. Our community was ready to build a new tomol, one that could be a hub of cultural activity, a place of education, a hope for the future.

With many hands to help build her, ’Elye’wun (swordfish) was born nine months later and her first launch was from Santa Barbara harbor on Thanksgiving Day 1997. As paddlers gently lifted the frail bodies of Chumash elders, Gramma Liz and Gramma Stella, into the ’Eley’wun, huge smiles broke out. “I would have gone to that launch if I had to crawl there!” - Gramma Liz Easter

The ’Elye’wun would go on to provide our people with opportunities for:

- Chumash tribes to gather together during the summer for “village hops”—near shore paddles at or between the coastal communities of Avila Bay, Hollister Ranch, Dos Pueblos, Goleta, Santa Barbara, Carpinteria, Ventura, and Malibu.

- Ceremonial paddle-outs for Chumash who have passed away.

- Generational maritime knowledge to pass down, become stronger, become more artistic, grow, evolve.

- Women, men, ’aqi (two-spirit), and children to paddle or spend time in the tomol and on the ocean.

- Our Chumash communities to create relationships with other maritime cultures, like the Hawaiians, the Pacific Islanders, and the Northwest Canoe people.

In 2001, ’Elye’wun became the first tomol to navigate across the 20 miles of open ocean to the Chumash Channel Island of Limuw since the time of Fernando Librado Kitsepawit’s youth in the 1800’s. In doing so, she sparked an annual tradition—The Crossing—an experience that generations of our people have embraced as a core part of our identity. We will always return to Limuw.

1997: The 'Elye'wun's base board is being laid on here, built on the jig created for the two tomol (Yuxnuc and 'Alolk'oy) that Marcus Lopez (not pictured here) built in 1996 for the Santa Barbara County Education Department. Pictured (clockwise from top): Jose Castillo, Peter Holworth, Roberta Cordero (Coastal Band) with misc film crew members. Photo: Julia Cordero

1997: Fitting the fifth and final row of planks in. Each plank has a groove down its center and an oak spline is inset between the planks--all of which was adhered together. Pictured: Jose Castillo, Alan Salazar, Cresensio Lopez (Coastal Band), Roberta Cordero (Coastal Band). Photo: Julia Cordero

1997: Fitting the fifth and final row of planks in. Each plank has a groove down its center and an oak spline is inset between the planks--all of which was adhered together. Photo: Julia Cordero

1997: Peter Holworth lays tape down around the cordage used to lash the planks together. Shipbuilder's epoxy was then applied to bind in the cordage lashing. Photo: Julia Cordero

1997: Grooves were cut into the wood around the holes where the cordage would be tied in, binding the planks together smoothly. The ends of the cordage are hanging down. Photo: Julia Cordero

1997: Cresensio Lopez (Coastal Band) pictured taping. Photo: Julia Cordero

1997: Eye of the 'Elye'wun, inlaid by abalone artist Cresensio Lopez. Photo: Julia Cordero

1997: Cresensio Lopez (Coastal Band) was an artist, Chumash cultural educator, and on the Board of Directors for the Santa Barbara Maritime Museum.

1997: Thanksgiving Day launch of the 'Elye'wun in Santa Barbara. Chumash community members and paddlers lead Grandma Stella Rivera (Coastal Band) to the tomol so she can go for a ride. Photo: Althea Edwards

1997: Thanksgiving Day launch of the 'Elye'wun in Santa Barbara. Chumash community members and paddlers lead Grandma Stella Rivera (Coastal Band) to the tomol so she can go for a ride. Photo: Althea Edwards

1997: Thanksgiving Day launch of the 'Elye'wun in Santa Barbara. Chumash paddlers lift Grandma Stella Rivera (Coastal Band) into the tomol so she can go for a ride. Photo: Althea Edwards

1997: Thanksgiving Day launch of the 'Elye'wun in Santa Barbara. Stella Rivera (Coastal Band) sits in front of her granddaughter while paddlers get the tomol ready to launch. Photo: Althea Edwards

1997: Thanksgiving Day launch of the 'Elye'wun in Santa Barbara. Stella Rivera (Coastal Band) sits in front of her granddaughter while paddlers get the tomol ready to launch. Photo: Althea Edwards

1997: Thanksgiving Day launch of the 'Elye'wun in Santa Barbara. Reggie Pagaling, Jaime Herrera, and Roberta Cordero (Coastal Band) steady the tomol for Grandma Liz Easter (Coastal Band). Photo: Althea Edwards

1997: Thanksgiving Day launch of the 'Elye'wun in Santa Barbara. Grandma Liz Easter (Coastal Band) ready to go for a ride. Photo: Althea Edwards

1997: Thanksgiving Day launch of the 'Elye'wun in Santa Barbara. Stella Rivera (Coastal Band) sits in front of her granddaughter while paddlers get the tomol ready to launch. Photo: Althea Edwards

1997: Thanksgiving Day launch of the 'Elye'wun in Santa Barbara. Stella Rivera (Coastal Band) sits in front of her granddaughter while paddlers get the tomol ready to launch. Photo: Althea Edwards

1997: Thanksgiving Day launch of the 'Elye'wun in Santa Barbara. Stella Rivera (Coastal Band) sits in front of her granddaughter. Photo: Althea Edwards

1998: The 'Elye'wun and it's crew join the Tongva for the second time at the Ti'at Festival in Long Beach. Photo: Althea Edwards

2012: Community gathering at East Beach, Santa Barbara. Photo: Sue Nakao

Greeting the Pacific Islanders, Malibu. Photo: Wishtoyo Foundation

Landing at Limuw (Santa Cruz Island) for the annual Chumash Crossing. Photo: Althea Edwards

The Crossings

Each year, long before the sun rises over the Pacific, a group of paddlers quietly pushes off the shores of Southern California in a tomol (redwood plank canoe), entering what our ancestors called wot’oyoy—the dark water. Sometimes, two or three tomols journey together. This is The Crossing, a powerful act of culture that reconnects people, place, and purpose across 20 miles of open sea to our island of Limuw (Santa Cruz Island). This roughly eight- to twelve-hour trip retraces the ancestral marine highway used for trade, ceremony, and kinship.

Started in 2001 by members of the Chumash community and the Chumash Maritime Association, The Crossing now happens annually, with paddlers journeying from Channel Islands Harbor in Oxnard to Scorpion Anchorage on Limuw. The tomols are crewed by rotating teams of paddlers from the deck of the NOAA Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary research vessel Shearwater. Organized by a consortium of tomol captains, support crew, and volunteers—and supported by extended tribal families and the National Park Service—The Crossing is much more than a one-day paddle. It involves months of preparation: tomol maintenance, physical training, ceremony, and logistics.

As the paddlers cut through the Channel, dolphins often join. Whales sometimes breach nearby. Seabirds circle above. The journey is watched—not only by the living, but by the ancestors. To witness a tomol cutting through the waters toward Limuw is to witness something sacred. And to paddle it?—that’s to become part of the sacred yourself.

But the journey doesn’t end on the island. When the tomol arrives, it is greeted with ceremony, song, and welcome by hundreds of Chumash families and friends encamped for four days. A fire is lit. Elders speak. Youth listen. Community gathers in remembrance and celebration. It is a moment of cultural continuity—a living expression of Indigenous sovereignty and presence.

This isn’t a reenactment, it’s reclamation and resilience. And for Chumash people, the Crossing is about much more than reaching the island—it’s about healing what colonization tried to sever: our connection to the ocean, to each other, and to the old ways.

The act of paddling a tomol across the Channel defies centuries of displacement, boarding schools, missionization, and environmental degradation. It proves that we are not relics of the past, but living, thriving people—innovators of maritime technology and caretakers of these waters since time immemorial.

Heritage Highlights

-

Name TBD ~ to be completed 2025

Builders:

Steve Villa (Chumash)

Marcus Lopez (Chumash)

+ Chumash community membersMilimolič hu ’Aqiwo’ (North Star) ~ completed 2025

Builders:

Marcus Lopez (Chumash)

Steve Villa (Chumash) / apprentice builder

+ Chumash community membersXax’ ’Alolk’oy (orca) ~ completed 2012

Builders:

Ray Ward (Chumash)

Ley Estrada (Chumash)

James Franco (Chumash

+ Chumash community membersMuptami (deep memory) ~ completed 2010

Builders:

Reggie Pagaling (Chumash)

John (??)

+ Chumash community membersLittle Sister~ completed 2010

Builders:

Ray Ward (Chumash)

James Franco (Chumash)Iša Kowoč (glistening salmon) ~ completed 2007

Builders:

Matt Ward (Chumash)

Mati Waiya (Chumash) / abalone inlay artist’Elye’wun (swordfish) ~ completed 1997

Builders:

Marcus Lopez (Chumash)

Roberta Cordero (Chumash)

Julia Cordero (Chumash)

Alan Salazar (Chumash)

Reggie Pagaling (Chumash)

Cresensio Lopez (Chumash) / also the abalone inlay artist

Peter Howorth

+ Chumash community membersYuxnuc (hummingbird) ~ completed 1996

Builders:

Marcus Lopez (Chumash)

Peter Howorth’Alolk’oy (dolphin) ~ completed 1996

Builders:

Marcus Lopez (Chumash)

Peter HoworthHelek (peregrine falcon/hawk) ~ completed 1976

Builders:

John Ruiz Thothokanayoh (Chumash) / also the abalone inlay artist

Joann Dixon (Chumash)

Darlene Garcia (Chumash)

Alan Whitebear Sulwasunaytset (Chumash) / also the abalone inlay

artist

Kote Lotah (Chumash) / also the abalone inlay artist

Peter Holworth

+ Chumash community members

Name Unknown ~ Completed in 1912, this tomol was not meant to be sea-worthy. It was an example made for display at the world exposition held in San Diego, California in 1915.

Builders:

Fernando Librado Kitsepawit (Chumash)

+ 5 men (names unknown) -

2000- present:

Captain (wot) is a title of responsibility and experience, not one of specific tomol ownership. The captains below have proved their leadership by captaining one—or many—of the tomols that have been built. Whether someone is a captain or a crew member, a man, woman, or ‘aqi (two-spirit)—they are all tomolelu (paddlers), and are greatly respected in our community.

Our crews are mostly a mix of different Chumash tribes, but our crews swell in the summer months for our near-shore village hops and our Channel Crossing to include many other California tribal people such as Tongva, Tataviam, Ajachemen, non-California tribal people, and non-Native people.Captains:

Marcus Lopez (Chumash) / retired

Ray Ward (Chumash) / retired

Reggie Pagaling (Chumash) / retired

Steve Villa (Chumash)

Marcus V.O. Lopez (Jr) (Chumash)Crew (just a few of the many):

Mike Cruz (Chumash)

Marcus V.O. Lopez (Jr) (Chumash)

Alan Salazar (Chumash)

John Bair

Oscar Ortiz

Tano Cabugos (Chumash)

Diego Rivera (Chumash)

Lacee Lopez (Chumash)

Toni Cordero (Chumash)

Matt Ward (Chumash)

Pachomio Sun (Chumash)

Jimmy Joe Navarro (Chumash)

Chuck Franco (Chumash)

James Franco (Chumash)

Ryan Ward (Chumash)

Lyle Ward (Chumash)

Izzy Morello (Chumash)

Lizzie Morello (Chumash)

David Jaimes (Chumash)

Maura Sullivan (Chumash)

Teotl Goitia

Tim Ochoa (Chumash)

Gabriel Frausto (Chumash)

Ray Lopez (Chumash)

Joseph Lopez (Chumash)

Eva Pagaling (Chumash)

Spenser Jaimes (Chumash)

Chimaway Lopez (Chumash)

Casmali Lopez (Chumash) -

Captain (wot) is a title of responsibility and experience, not one of specific tomol ownership. The captains below have proved their leadership by captaining one—or many—of the tomols that have been built. Whether someone is a captain or a crew member, a man, woman, or ‘aqi (two-spirit)—they are all tomolelu (paddlers), and are greatly respected in our community.

Our crews are mostly a mix of different Chumash tribes, but our crews swell in the summer months for our near-shore village hops and our Channel Crossing to include many other California tribal people such as Tongva, Tataviam, Ajachemen, non-California tribal people, and non-Native people.

Captains:

Marcus Lopez (Chumash)

Perry Cabugos

Crew (just a few of the many):

Reggie Pagaling (Chumash)

Steve Villa (Chumash)

Alan Salazar (Chumash)

Harry Pagaling (Chumash)

Julia Cordero (Chumash)

Burt Barlow

Dan Umana

John Bair

Jackie Shinehart (Chumash)

Stacy Thompson (Tongva)

Rick Mendez (Tongva)

Rhonda Robles (Tongva)

Oscar Ortiz

Mike Cruz (Chumash)

Elaine Cruz (Chumash)

Marcus V.O. Lopez (Jr) (Chumash)

Dennis Kelly (Chumash)

Tano Cabugos (Chumash)

Diego Rivera (Chumash) -

Captains:

John Ruiz Thothokanayoh

Victor Slo’w GutierrezCrew:

Joseph Estrada Thot

Manuel Estrada Akhewo

Frank Gutierrez Kuic

Frank Gutierrez, Jr. Tomoloc

John Sespe Gutierrez

Raymond Chechihoh Gutierrez

Kote Lotah

Alan Whitebear Sulwasunaytset -

Aliseyu

Almuastro

Alsenio

Américo

Bernardino ’Alamshalalɨw

Bernardino Pashe

Juan Cansio

José Carlos

José Diego

Ebaristo

Felipe ’Alilulay

Francisco

Francisco Kuliwit

Francisco To’qoch

Juaquín

Juan Francisco

José

Ignacio

Ivón José

Kaku’araut

Laudenzio

Leandro ’Alow

Liwinaishu

Fernando Librado Kitsepawit

Lorenzo

José Antonio Mamerto Kitsepawit

Odón María

Mateqai

Mauricio

Millán

Mushu

Paisano

Palatino Saqt’ele

Pánfilo Tomolelu

Piyaraut

Silkiset

Silverio Konoyo

José Sudón Kamuliyatset

Sulupiyauset

Sulwasunaytset

Teodoro Piyokol

Timiyaqaut

Tomás Chnawaway

José Venadero Silinahuwit

Vicente Qoloq

Ysidro

Tomol, Tule Boats, Dugout Boats…and More!

Tomol plank canoes are at the heart of our ocean maritime traditions. But our tule boats, dugout canoes, and sheath canoes were the best way to navigate the near-shore waterscape of our ancestors, which was rich in rivers, marshes, estuaries, and lakes.

Tule Boat

A tule boat (stapan hil tomol) is made from long bundles of dried tule, lashed together expertly and formed into a beautifully arched boat that is both buoyant and light. The outside is coated in tar for durability.

Dugout Canoe

The dugout boat (’a’xipe’neš) was made from a single tree of old growth black cottonwood that was hollowed out and shaped on the outside. Thirty feet in length and three to four feet wide, the underbelly was curved (like the tree it was made from). Both stern and prow were pointed, ending in blunted tips. The last one was made in 1854 in Goleta, just north of Santa Barbara.

Sheath Canoe

In the late 1700’s and early 1800’s, when Russian seal hunting companies were leading excursions to hunt seals around the Chumash Channel Islands, they brought Aleut hunters down with them. All cultures borrow and adapt, and when Chumash boat-builders were exposed to the hide boats that Aleut seal hunters used, they were inspired. The Chumash sheath boat was born: a framed boat with ribs, in the shape of a tomol with a curling willow edge to create the “ears.” Covered in great white shark hide and and lashed with oxhide, this boat was probaby incredibly fast and light. This maritime vessel hasn’t been made since the 1800’s.

Our resources are scarce.

Four hundred years of European colonization has terraformed the Chumash landscape through livestock grazing, dam construction, deforestation, oil drilling, wetland drainage, mining, and urban development. This dramatic reshaping has nearly eliminated the vital materials we need for our traditional watercraft—tule boats, tomol, dugout boats, and sheath boats. And it’s erased the waterways we use these vessels on.

Today, tule reeds survive only in small, protected preserves, accessible through formal agreements and careful stewardship. Long, straight willow branches grow only in ONE place nowadays—along the Santa Clara River—Southern California's last un-dammed waterway. The widespread logging of redwood forests in the Northwest has ended the natural process of fallen trees drifting southward to our coastal inlets. And the old growth forests of cottonwood are gone. Our community continuously struggles to protect these vanishing resources, to maintain our access to ancestral waters, and to secure spaces where we can build and preserve our maritime heritage.